Running a restaurant used to be easy.

An owner and a chef, or a chef-owner, got a room and a kitchen and fitted them out. They wrote some menus, culled together suppliers, pulled together a wine list, and they cooked lunch for paying customers from Monday to Friday, and cooked dinner from Monday to Saturday. On Sunday, the chef and the staff rested, and did the VAT.

From the time of the earliest Parisian restaurants – created around about 1750, when a “restaurant”, a broth made with chicken or beef, was actually what you ate – through the great culinary chroniclers like Escoffier of The Ritz, and onto Derry Clarke in L’Ecrivain, precious little changed in the world of restaurants – chef; menu; wine list; lunch; dinner; 12.5% gratuity will be added to your bill.

Restaurants were judged on the quality of their cooking, and thereby spent virtually no time on classic business ideas such as marketing; brand building; customer satisfaction; communications; post-sale service; innovation.

Such innovation as occurred was strictly culinary – classic cuisine gegat nouvelle cuisine; nouvelle cuisine begat molecular cuisine.

“Oh, I never went in for any of that marketing talk”, the grand-dame of Irish cooking, Myrtle Allen of Ballymaloe House, said to me more than a decade ago. “I just tried to do the best I could and hoped someone would like it.”

Today, virtually everything in the world of restaurants has changed.

Ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-changes.

The changes began early on in the first decade of the new century. People had more money to spend on restaurant food, but they wanted to spend it their way.

In August 2003, the long-time restaurant reviewer of The Financial Times, Nick Lander, wrote that “restaurateurs must realize that the rules governing their profession for the last 200 years no longer apply”.

For Tom O’Connell, of O’Connell’s of Donnybrook, “The changes in the restaurant business over the last decade have been consumer-driven: people began to tell restaurateurs what they wanted them to do, and that was not the case before.”

The twin cams of the restaurant offer today, says O’Connell, “are offering local Irish foods, and real value for money. When we opened in 1999 we had our producers listed on the menus, and yet I spoke to a restaurateur recently who told me he had just switched to Irish chicken! It wasn’t free-range or organic or anything, just Irish, and yet he thought it was a big deal! So, some people still don’t get it”.

Donal Doherty, of Harry’s Restaurant at Bridgend in Donegal, noticed a new focus on local ingredients after Lehmann Bros and the 2008 crash.

“Even though we used Inishowen foods, the appreciation wasn’t there. After 2008 it accelerated, and people began to want to know where and how far their money was going.”

Mr Doherty has upped the ante with local produce: “I have shorthorn beef on the menu now, next week it will be Dexter beef. I have 5 farmers supplying me with rare-breed pork. We were the first to use dry-aged beef, but now everyone claims to be doing that, so we have to move on. We pay more to our producers because we pay for taste, we pay to ensure customers return, we pay more so that the experience is memorable.”

One other factor that has given Harry’s a lift is social media. Mr Doherty, a widely-admired practitioner, estimates the tweets and Facebook add 10% to Harry’s bottom-line. “We used to spend maybe €4k a year on advertising: now we don’t have an advertising budget; not a cent. But there is an art to it; bad places come out of social media very badly.” What is of equal importance to Harry’s, however, is the ability through social media to talk with their suppliers, colleagues, and others in the business.

“People in the business in Donegal used never share information or experiences: now they do.” When Mr Doherty organized the Inisfood Festival last year, virtually everything in the weekend event was brought together through tweets.

Social media has also enabled pop-up restaurants to open, scoring an audience from postings and tweeting, setting an information virus buzzing amongst followers.

The Multi-Platform Restaurant

But if restaurateurs have had to learn to listen more carefully to customers, and to communicate more directly with them, they have also had to expand the very concept of the restaurant itself.

For restaurateurs like Paul and Maire Flynn, of The Tannery in Dungarvan, their initial restaurant space, and its lunch-and-dinner formula, has expanded in recent years to include two townhouses with accommodation for guests, a smart cookery school, and an extensive garden with poly tunnels beside the cookery school where the raw ingredients for the restaurant and school are produced.

Restaurateurs have similarly discovered that a restaurant can be a moveable feast. Both the Wheeler family’s Rathmullan House, of Donegal, and Paul Cadden’s Saba, of Clarendon Street, Dublin – which already boasts a Saba-to-go outlet and wine shop in Rathmines and a cookery school – have enjoyed huge success by transporting their kitchens to the Electric Picnic Festival in recent years. The mountain, it seems, must be able to go to Mohammed.

Both Avoca Handweavers and Donnybrook Fair, whose restaurants form a significant element of a mixed-retail-lifestyle experience, have been enjoying profitable trading in their last financial year.

Avoca reported profits of €1.64m on revenue of €48.6m, and almost immediately opened a new restaurant with more mixed food retailing in Monkstown, Co Dublin, creating 80 new jobs. Simon Pratt of Avoca reported that 2011 had been even better than the figures up to the end of January 2011.

Joe Doyle’s Donnybrook Fair, with four outlets, had turnover of almost €21.8m, and profits of €472,600, a sharp turnaround from a previous reported loss of €815,000. Diversity is clearly working for top-end food retailers.

Where to Next?

“Everything is going to get more casual” says Donal Doherty.“You are already seeing that in Dublin with pop-ups like Crackbird, and I can see a situation where people, over the course of an evening, move from restaurant to restaurant. The three-course menu – starter-main course-dessert – is going out the window, people are into sharing plates, and going to places where there won’t be any menu”.

“A relaxed, coffee shop culture, where simple things are done well, is what we are going to see more of”, says Tom O’Connell. “I mean, I would walk 20 miles just to eat the Victoria sponge cake Eileen Bergin serves at The Merrion Tree in Mount Merrion.”

Personally, I think we will soon see more single-theme restaurants – rare-breed beef only; ham and cabbage only; wild food only; food only from Tipperary.

In The New York Times recently, restaurant reviewer Pete Wells devoted his weekly review to Federal Donuts, a corner joint in Philadelphia. Federal Donuts serves doughnuts, and halves of fried chicken. They make 80 halves of chicken a day, and about 150 doughnuts. When the birds and the bakes are all sold – usually by early morning – they close until the next day. Now, that’s niche cooking.

In Killarney, Rob O’Reilly and Barry McBride’s Pay As You Please restaurant has managed to sustain a workable formula where the punters pay what they feel the food was worth. “People have been amazingly generous”, says O’Reilly, and when I visited in December last, PAYP was buzzing.

The recession has been hard to restaurateurs – smaller profits as people drink less; little if any business account spending; customers endlessly demanding more value.

And yet, in forcing restaurateurs to be more imaginative, forcing them to think sideways and to broaden the ways in which they conceive their offer, the recession, ironically, has been the best thing to have happened to Irish restaurants in yonks.

This article was first published in The Irish Times Business+

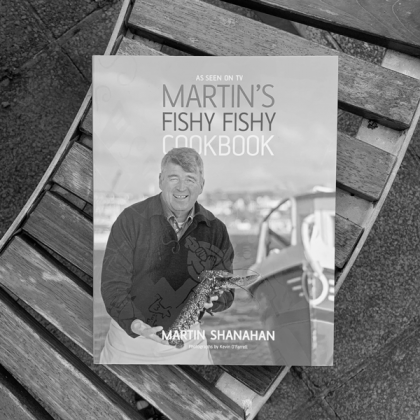

Photo by Mike O'Toole www.mikeotoole.com